Excerpt From:

Listlogging, Petty Squabbles, and Big Egos:

A History of the DXing Hobby 1920 to Present

by Jack Mann

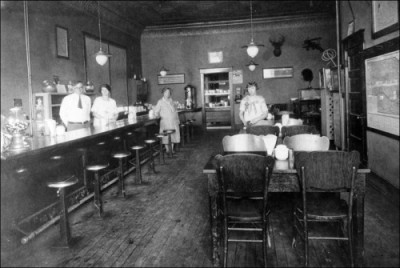

The Chrome Diner Radio Club (1933-1982)

The Chrome Diner Radio Club was one of the most important U.S. radio clubs for several decades and clearly the premier club during the 1930s and again in the 1950s. The CDRC had its beginnings in late 1931 with monthly meetings held by a casual group of radio hobbyists in the Lancaster and Chester county area of Pennsylvania. As the topic of converstations at their meetings frequently strayed from radio to matters of a more delicate nature, by early 1933 the group had been banned from three area libraries and two public parks. The group was about to disband when it got an offer from newcomer Bill Pugh. Pugh was the owner of the Chrome Diner in the town of Chrome in southern Lancaster county, not far from the Maryland border, and he offered to host the meetings in the back room at his restaurant. He had seen how most of the members ate and drank, and he knew a good business opportunity when he saw one.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Not surprisingly, the first meeting of the Board of Directors also saw the first major conflict. While Elmer Dixon and Tony Poletti wanted the bulletin published every week during the DX season, Bill Pugh and Roy Felton prefered every two weeks. Amazingly this was settled by a peaceful compromise, rather than the name-calling and food fights that soon became common, let alone the knife-fights that came to characterize board meetings during the club's final few years in the 1980s. (That was probably a good thing, given Poletti's reputed proficiency with a switchblade.) The four directors settled on issuing the bulletin every ten days. So for the next sixteen years between October and April it came out on days ending in 5 (the 5th, 15th, and 25th), except for February when it was only published on the 12th and the 22nd to honor the birthdays of Abraham Lincoln and George Washington. While nominally published monthly in the summer, in most years Pugh never got around to putting the bulletins together until early September, when he published one super-sized issue.

|

|

|

With a large cadre of local members, the CDRC was soon putting out a quality information-packed bulletin, which in turn attracted more distant members elsewhere in North America and overseas.

In these early years, the connection between the Chrome Diner and the Chrome Diner Radio Club was more than just a shared name and a meeting palce. While membership was nominally two dollars a year, anyone who lived close enough to do so could get a free year's membership from Pugh by just arranging to wash dishes or bus tables for three four-hour shifts at the diner. (As the normal rate of pay for dishwashers was twenty-five cents an hour, Pugh made quite a profit on his generosity.) In 1934 at least fifty members paid their dues this way and by 1936 the number was over 200. Shifts had to be arranged in advance and most issues of DX Listening Digestion during the 1930s included upcoming dishwashing schedules as well as a list of empty available slots. Some distant members would sign-up for an entire weekend and in exchange for an extra four-hour shift, Pugh would let them sleep in the club meeting room. From 1935 to 1938, member Byron Cushing hitchhiked from Omaha to Chrome every year to work the third weekend in May after his classes at Creighton College finished for the year.

Bulletin Content and Columns

Like the dishwashing schedules, the connection with the Chrome Diner was clear in every issue. For example, in return for free use of the meeting space, a full page ad for the Chrome Diner appeared in every issue of DX Listening Digestion during this period. Still, the bulletin had most of the columns that would be found in an all-band radio club of the era.

|

|

|

Ham Dinnerwas a column for amateur radio operators. At the end of each year, Bill Pugh chose a Most Valued Contributor from the Ham column for that past year and awarded the winner a coupon for a free ham dinner at the Chrome Diner. This was highly prized as Bill was not known for giving things away. Several members got their licenses simply for a chance at that. The Ham Dinner column was started in January, 1934 by Ernest Holloway who edited it through July, 1937. Over the next four years it passed through a succession of five editors - Ward Porter, Vince Herman, George Maxwell, Andy Fletcher, and Leo Haywood - until being dropped during the Second World War when amateur radio activity was curtailed.

|

|

|

Main Course) had the remarkable record of not changing editors for its entire history from the first issue on November 5, 1933 until the club dissolved in 1982. It was also unique in that during the entire period it was jointly edited by two people - lifelong roommates Clarence Stover and Arthur Brumbaugh of Talleyville, Delaware. While continuity has many positives, the one drawback of entrenched editors is resistance to change. As a result,

Main Coursedidn't switch from using wavelengths to kilocycles until 1967. Also, every column ended with a logging for fictitious station HORE in David, Panama, which Clarence and Arthur seemed to find funny.

|

|

|

|

|

|

DXers' Dateline, which appeared six times a year from 1935 until 1941. The premise was very simple - the best way to prevent family events from interfering with DXing was to have DXers in the family. The column, edited by the ever-popular Clarissa Gilman, was used to set up blind dates between single (male) members and the single sisters, daughters, and female cousins of other members. Clarissa understood that young women with a radio nut already in the family might be cautious about marrying another one. In the first column of every year, she promised the ladies that

No man's name will ever appear in this column until I have thoroughly interviewed him and ascertained that he is good husband material in every way.

So respected was Clarissa in the club, that many of the already-married members requested retroactive interviews, but it's not known how many of those requests she honored. Comments in several letters in the Clarissa Gilman Papers at Swarthmore College indicate that Clarence Stover and Arthur Brumbaugh also helped in screening the men being considered for this column, although just what role these two confirmed bachelors had isn't clear. With most young men on their way to war, the column was dropped in early 1942, but Clarissa claimed that no fewer than fifteen marriages had come out of her efforts.

|

|

|

Awards And More

|

|

|

The country list used for the Chrome Diner DXer award is believed to be the first radio country list created by DXers for DXers. The list was updated each March when Bill Pugh had new menus printed with new menu items (and prices). (There were so many complaints in 1938 when Brazil was dropped from the list after Bill stopped putting Brazil nuts on the banana splits, that he added them back to the menu in May.)

|

|

|

Indeed, one of the things that made the Chrome Diner Radio Club so well known was Bill Pugh's knack for merchandising the club. In 1935, Pugh began selling dinner plates with a huge CDRC logo in the middle. These sold well enough, but members complained that they couldn't see the logo when the plate was covered with food. Pugh gave the matter some thought and two years later (after the plates had sold out), introduced what was to become a proud hobby tradition - the DX club coffee mug. At least three different designs were issued by Pugh over the next four years. The DX hobby would see nothing surpassing this until the birth of a particular Canadian club nearly four decades later.

Local Chapters

|

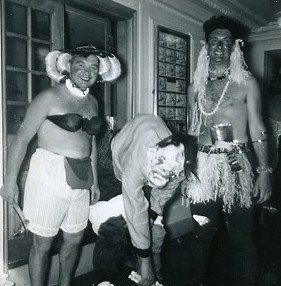

Best Dressedin 1939 |

Typically these chapters met at local diners, but in their reports published in DX Listening Digestion, they often lamented that it just couldn't be the same as meeting in the real Chrome Diner. In 1936, Pugh began selling his own line of Chrome Diner canned goods via mail order. After that most local chapters met in member's homes to share a meal of Chrome Diner canned hash or Chrome Diner canned tomato soup with Chrome Diner tinned butter cookies for dessert. All Pugh did was buy canned goods at wholesale and replace the labels with his own (after doubling the price with 10% going to the club). But, it was a highly successful way of giving members in places like Wichita, Halifax, and Mobile the sense of being a part of the Chrome Diner itself.

|

|

|

Truly one of the most unique local chapters was that formed in 1937 at the Convent of the Order of Saint Agnes in Strawberry Point, Iowa. At first the sisters were just looking for help in listening to broadcasts from the Vatican, but they soon saw that understanding world events via shortwave listening gave them more to pray about.

|

|

|

The War Years

Following Pearl Harbor, in early 1942 Bill Pugh closed the diner and enlisted in the U.S. Army as a cook. Stanley Cushman of nearby Homeville agreed to take over Pugh's duties as publisher. However, this did not lead to a change of address or name. The building the Chrome Diner had been located in was owned by Pugh's brother-in-law, Bill Greble, who had his law office on the second floor. Although Greble was never a DXer, he had formed close friendships with many of the core members of the Chrome Diner Radio Club (especially Clarissa). Unable to rent out the first floor due to the war economy, Greble agreed to let the club continue meeting in the back room and also agreed to let the club continue to use the same mailing address: The Chrome Diner Radio Club, 102 Greenhouse Road, Chrome, PA.

|

|

|

Of course fewer members meant fewer contributors and Cushman often stuggled to fill the pages of DX Listening Digestion. Several columns disappeared when their editors joined the service and no replacements could be found. Other were irregular because of lack of material. In the first four months of 1943 only one thin issue of DX Listening Digestion was published and from all appearances the club was about to go under. In May, with the second issue of the year, Cushman published a lengthy front page plea for member contributions. When the pleas didn't work, Cushman and Poletti went to offering small bribes and then quickly escalated to threats. Once members learned that Poletti's brother Vito had numerous connections to the Philadelphia Mafia, the threats worked and the club survived.

One of the greatest hardships was the shortage of staples in 1943 and 1944. Since Cushman wasn't able to staple the pages together, there were problems with lost pages in the mail. And in February 1943 an uxpected blizzard hit the same day as the monthly meeting and twenty-two members spent the next three days in the meeting room living off a case of Chrome Diner canned hash they found behind a door.

The Post War Era

The period of 1945 to 1950 was one of major transitions for the CDRC. In July 1945, Bill Greble informed the club that he had found a tenant for the old Chrome Diner storefront and that the club would have to find another location for its meetings. When Tony Poletti initially asked if they could continue to use the Chrome mailing address and just send someone to pick up the mail once a week, Greble refused. Then Clarissa Gilman volunteered to be the one to pick up the mail once a month and Bill gave in.

|

|

|

DXers'Datelinein November, 1945. As to Bill Pugh, at the end of the war he was stationed in Trieste, Italy where he met and then married a Slovenian refugee. The couple remained in Europe, but Bill's importance to the North American DXing hobby wasn't over.

Without a permanent location, monthly meetings were no longer possible. Instead, several picnics were held at area parks in the warmer months and beginning in 1947 an annual convention was held, usually in Lebanon, Pennsylvania (home of a famous luncheon meat that had been served in the old diner). After an unfortunate incident at the 1947 convention a rule was made that members had to be at least 21 years of age to attend.

|

|

|

While the CDRC prospered immediately after the war, it was not able to recover the position of premier North American radio club, which it had undisputedly held through most of the 1930s. The old Transcontinental Radio Club (TRC) and a new club, the All Wave Listeners' Union (AWLU), founded in 1947, were more vibrant and had more members. Outside of the tri-state area around southeastern Pennsylvania, most of the best DXers in North America participated in the other two clubs, but did not join the CDRC. This in turn meant that newer hobbyists were more apt to join the TRC or AWLU. After reaching over 800 members in 1947, the Chrome Diner Radio Club soon dropped to around 400 members, most of whom had been around since the 1930s. Without the diner, the Chrome Diner Radio Club just wasn't the same. In a June 1950 editorial in the pulp hobby magazine Big Knobs, Ralph Norris wrote that the CDRC was no longer relevant in the listening hobby.

|

|

|

Floyd McGee had joined the CDRC in 1934 as a high school student, faithfully working his three four-hour shifts washing dishes. A shy bookish kid, McGee stayed on the periphery (and well away from Clarissa). He continued to be intermittently active through college. In 1942 he earned his Master's degree in Psychology from the University of Pennsylvania and was immediately hired by the OSS (Office of Strategic Services - predecessor to the CIA). During the war he was deeply involved in disinformation and black propaganda. After the war he earned his PhD and in 1949 was hired as a professor at small Haskins College in Coatesville not far from Chrome.

At CDRC social events McGee had formed an unlikely friendship with Marcus Schwenke. A mail clerk for the Philadelphia Prosecutor's Office, Schwenke was described as a large gruff man with hairy arms, oversized ears, and a leering grin. The sight of him frightened small children and not a few adults, not to mention any livestock that had previously had the misfortune to wander in his vicinity. The reader should consider himself fortunate that no pictures of Schwenke are known to have survived. But then, maybe none were ever taken.

|

|

|

The nature of our hobby is that clubs come and go. Few can maintain the momentum to stay relevant for decades. Yet, never has our hobby seen two major clubs totally disintegrate in the period of one year, as happened in 1954 with the Transcontinental Radio Club and the All Wave Listeners' Union. Although both bulletins had been highly regarded for their quality and accuracy, suddenly in 1954 all the columns in both bulletins began having serious quality control problems as long-time members reported items that turned out to be total fantasy. Editors and senior members pointed fingers at one another and nasty letters went back and forth. By mid-year experienced DXers were leaving each club by the dozens. The TRC published its last bulletin in Octobr 1954 and the AWLU held out another month before closing its doors.

During this troubled time, Cushman, Poletti, and McGee had made a point of reaching out to the members of these dissolving clubs. They published editorials in DX Listening Digestion defending those DXers whose reputations has been besmirched by the TRC and AWLU. Their efforts paid off in that by the end of 1954 over 300 of the best DXers in North America at the time who had not been CDRC members now were. The Chrome Diner Radio Club was once again the premier radio club in North America.

|

|

|

In 1956 a new column DX Eavesdropper

was started for members who wanted to gossip about the converstations they heard while monitoring maritime radio-telephone calls. Because of the increased difficulty in international medium wave DX in North America, in October 1956 Clarence and Arthur announced that for country-counting purposes they would extend the MW band to 6 MHz.

With few eligible members of the right age, Clarissa Gilman published the last DXers' Dateline column in April 1957. Included in it were a complete list of the 43 known couples that had joined in marriage through her column in its two periods (1935 to 1941 and 1946 to 1957) as well as a list of the 364 single DXers she had interviewed for the column over the years. (She also mentioned something about circulating a list of the 23 who had been screened out of the column after being interviewed by Clarence Stover and Arthur Brumbaugh unless she was able to purchase the new Cadillac she wanted, in which case it would probably slip her mind.)

|

|

|

The Crisis of 1959

|

|

|

The financial meltdown and Poletti's resignation were just the beginning. The stress soon caused Marcus Schwenke to suffer a nervous breakdown and then two months later, become a Jehovah's Witness. In order to purify his soul, Schwenke wrote a long resignation letter telling the unknown story of what had happened to cause the downfall of the Transcontinental Radio Club and the All-Wave Listeners' Union. This in turn led to the resignation of Floyd McGee and Stanley Cushman.

As Schwenke recounted it, Floyd McGee had drawn on his skills from the OSS to mastermind a scheme beyond anything the DXing hobby has ever seen. In late 1951, McGee created two dozen fictitious DXers, in two dozen different towns in the Eastern US, and joined eighteen of them to the TRC and eighteen to the AWLU. All soon became regular contributors of average but dependable material and soon became known names in both clubs. At least one was even asked to take over editorship of a column, which he declined.

What made this possible was Schwenke's job as mail clerk for the Philadelphia Prosecutor's Office. So that the letters from the bogus DXers arrived with the correct postmark, and thus looked authentic to the editors, Schwenke had the letters posted by police departments in the right towns. The police departments were told this was part of an on-going investigation by the Philadelphia Prosecutor's Office and they should not mention a word of it. Likewise, Schwenke arranged for the police departments to set up dummy addresses in their towns, with all mail forwarded to Schwenke. Schwenke said that Tony Poletti knew all about McGee's scheme, but refused to let club finances be used as he wasn't convinced that it would work. Also according to Schwenke, a third DXer assisted McGee, but he refused to name who. Everyone assumed it was Stanley Cushman.

|

|

Did This Club Deserve To Die? |

|

|

This One Did |

What was never explained was just how McGee financed all this on his professor's salary. While Schwenke's mailings were paid for by the Philadelphia Prosecutor's office, no one knew just where McGee came up with the money to pay for so many DX club subscriptions. It's now commonly accepted that Stanley Cushman was innocent of any involvement in McGee's dirty work. But, who was the third unnamed DXer mentioned by Schwenke? Today, most fingers point at none other than BLANDX cofounder George LeBouton. When he joined the CDRC as a high school student in 1951 LeBouton lived in Coatesville, not far from McGee, and in 1953 he started at Haskins College, where he had a close relationship with Professor McGee. We now know that George LeBouton was a highly skilled burglar and police records from the time list a large number of unsolved burglaries in Coatesville and at Haskins College.

The Zombie Years - 1960 to 1982

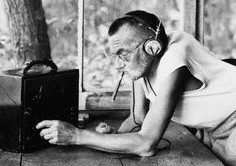

Most of the DXers who had joined the CDRC after the disintegration of the TRC and AWLU left the Chrome Diner Radio Club in disgust by the end of 1959 and most of the younger members who had joined followed them. Membership in the CDRC had become a badge of shame. In fact, a number of international broadcasters announced that they would not QSL reports from people who continued to belong to this club. But, a few members hung on and somehow Oscar York and Jim Russo, with help from Clarence Stover and Arthur Brumbaugh, managed to keep what was left of the club together. By the end of 1960, membership had dropped to about 150 and it never rose above 200 for the remaining two decades. DX Eavesdropper

and Stover and Brumbaugh's medium wave column were the mainstay of the bulletin for the final two decades. With the QSL boycott, SWBC DX coverage never again figured prominently in DX Listening Digestion.

|

|

|

|

|

|

As to the Chrome Diner Radio Club, it never recoverd from its pariah status. However, that status did result in a final brief glory period. Around 1978, the CDRC was rediscovered by teenage punk-rock fan MW DXers who found the CDRC's pariah status appealing. By 1980, the CDRC had the odd distinction of having 55% of its members over the age of 60 and 40% under the age of 25. The younger members soon took over most of the club's leadership positions and gave DX Listening Digestion an outlandish punk look with help from, of all people, Clarence Stover and Arthur Brumbaugh. But, most old members were not pleased and dropped out, sending the club to the verge of bankruptcy. This lead to a series of knife-fights at the Board of Directors meetings, culminating in the one at the July, 1982 meeting when the police were called in and the entire Board and publishing committee was arrested, making the July, 1982 issue of DX Listening Digestion the last one.

The BLANDX Connection

As we all know, the founders of BLANDX came from CDRC members who left the club after the scandal of 1959. For many years the standard accepted story of the founding of SASWA (the official club name for BLANDX until 1996) has been Dillon Hollister's excellent A History of SASWA, which can be found on pages 4-6 of the June 1987 issue of BLANDX. In there Dillon states that SASWA ... was founded in the back room of Bill's Bar & Slovenian Hamburger Inn in Intercourse, PA sometime during the week of August 7-13, 1963. Unfortunately, the exact activities that went on in that room to lead to the foundation of SASWA will never be known. Nor will how the five founding members woke up on the morning of August 14, 1963 in a community center in Happy Jack, Arizona with an edition of the SASWA By-Laws and 50,000 copies of the August, 1963 edition of BLANDX.

The five founding members were Elmer Dixon, Elmer's sixteen year old nephew Jack Bradbury, the infamous George LeBouton (see the aforementioned article), Andy Fletcher, and Jack's classmate Al Weldon. None of them were ever able or willing to provide more information to what Dillon wrote in his article. However, shortly before his October, 2002 death, Elmer Dixon recounted to me a few brief details of the secret story of what really happened - on the condition that I promised to keep it secret until his wife had also passed away. In January 2009, Maggie Dixon departed this world and I am able now to tell Elmer's story on the founding of BLANDX.

After the meltdown of the CDRC, a core of disaffected members began meeting regularly on Wednesday evenings in Bill's Bar and Slovenian Hamburger Inn. Usually eight to ten would show up, but on this particular evening only Elmer, George, and Andy made it, although Elmer brought along his nephew Jack and his friend Al, each of whom had been DXing for about two years. Jack had some great ideas about how a financially-successful new club could be structured, and George LeBouton said he had a source of seed money to get it started. That evening they put together the first rough draft of the SASWA by-laws. At 11 p.m. they decided to celebrate by driving to Atlantic City, New Jersey to visit a certainhousewhich Andy Fletcher knew about. LeBouton stayed behind, saying he had some business to attend to but would join them the next morning.

The original plan was to just stay one night in Atlantic City, but George arrived with a lot more seed money than anyone had expected so they decided to extend their stay to a week. But, our five founders hadn't come to Atlantic City to just screw around. Jack Bradbury spent his afternoons finely tuning the by-laws into the ones we are still using today with the intricate international financial connections that have turned BLANDX into the multi-million dollar corporation that it is. Meanwhile, the four others concentrated on putting together the first sixteen page mimeograph issue of BLANDX, mostly by plagarizing several other bulletins that Elmer had in the trunk of his car.

Now, those of us who know Jack Bradbury today will find it hard to believe that Jack Bradbury (of all people) was the brains behind setting up the entire club. But, you have to remember that this was before Jack fried his brain on sex and drugs in the early 1970s.

As to the Arizona story, our heroes realized that they would have to tell something other than the truth to their wives and mothers when returning home. So, they made up the story about waking up in Arizona and implied that they had been kidnapped by aliens. Of course, it helped that Elmer's wife and Jack's mother both belonged to a local UFO study group.

There are still many unanswered questions about the founding of BLANDX, but sadly there is little chance of ever learning more. Andy Fletcher took what he knew with him to the grave in 1993. Jack Bradbury doesn't remember anything that happened before 1972. George LeBouton hasn't been seen since he absconded with the club finances in November, 1971. No one has heard from Al Weldon since he went into the FBI Witness Protection Program in 1978. So, unless either George or Al reappear or someone finds that lost diary of Jack Bradbury's that is rumored to exist, this might be all we know of the founding of BLANDX.

|

|